WHY THE ARTS ARE A CENTRAL FORCE IN THE ECONOMY

WHY THE ARTS ARE A CENTRAL FORCE IN THE ECONOMY

By David Throsby | Wednesday February 20 2013

Fashion, architecture and computer games are all industries that depend on the arts economy.

In recent years there has been a growing policy interest in the economic potential of the arts. Economic policy in many countries in Europe, Asia, South America and elsewhere is paying increasing attention to the idea of the ‘creative economy’, the proposition that there exists in the economy a group of so-called ‘creative industries’ whose contribution to GDP, employment, exports etc. is growing more strongly that in traditional sectors such as manufacturing. Investment in these industries, so the argument runs, will pay handsome dividends in revitalising sluggish economic performance. This trend has had direct implications for the arts because the cultural industries, which include the arts, are a significant component of the creative economy.

Some people, including many artists, feel uncomfortable with a trend towards an emphasis on the economic role of the arts. The creative arts, they argue, are not an industry – artistic production has its own rationale that has nothing to do with economics. Artists are involved in pursuing whatever is their creative vision, and they resist the implication that their work can be treated simply as a commodity. So the question arises: How can we see the creative arts as contributors to the economy, but do so in a way that doesn’t constitute a sell-out to ‘economic rationalism’?

I suggest that it all depends on how you conceptualise the arts as a component of the cultural sector in the contemporary economy. We can interpret the contribution that the arts make to the economy as arising from the fact that they depend on creativity – the arts generate creative ideas and creative processes that feed other industries in the cultural sector like television, publishing, etc. and may flow on to other industries far removed from culture. The arts also train people in creative skills and develop creative talent that can be applied in many other industries.

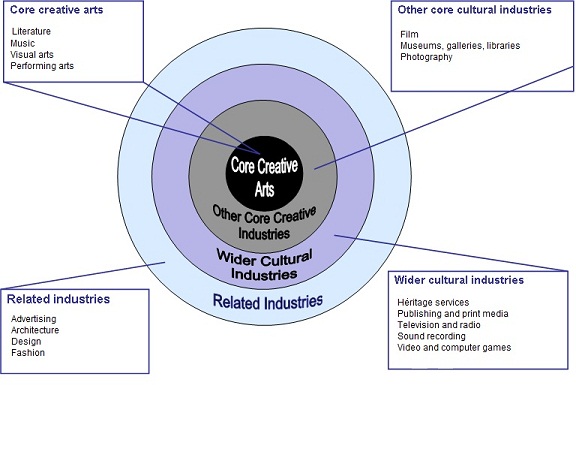

So an appropriate way to interpret the arts in the economy is to put them at the very centre of a production system that derives benefit from the things the arts do. I have suggested a model of the cultural sector built along these lines. It sees the cultural industries as a series of concentric circles with the creative arts as the core, and with other industries producing output with cultural content represented as the various layers or circles around the core. The layers represent increasingly commercial industries as we move outward through the circles. The industries are classified into four groups ranging from industries with very high cultural content in the centre circle (music, theatre, visual art, etc.), to industries with a very small cultural content relative to commercial content in their output in the outermost circle (fashion, architecture, etc.).

The logic of this model is that ideas generated in the core diffuse outwards through the layers and beyond, stimulating creative output and innovation in other industries and sectors. Likewise creative talent and skills nurtured in the core find application in other industries through the movement of creative workers – artists, for example, may employ their creative skills in other industries in various ways such as visual artists designing websites, or actors involved in management training in big corporations, or craftspeople developing new materials and processes for use in industry.

So the message is this. Of course the arts are to be celebrated, encouraged and facilitated for fundamental artistic reasons, as well as for the wide range of cultural and social benefits that they bring. But we need to recognise that in addition they are a powerful economic sector, and the model of concentric circles helps us get this role into perspective. Not only do the creative arts deliver benefit to the economy through their contribution to GDP and job creation, but also they act as a source of creative ideas, skills and talents that have direct impacts on economic performance in the whole economy. This is as true in Australia as in any other country. The Discussion Paper for the National Cultural Policy that was released last year made much of these economic considerations in its discussion of government policy towards the arts. It seems likely that these ideas will help to shape the National Cultural Policy itself which we hope will be released some time soon.

David Throsby | [email protected]Professor David Throsby is Australia’s leading cultural economist. He is Professor of Economics at Macquarie University, has been a consultant to the World Bank, the OECD, FAO and UNESCO, and has chaired three Prime Minister’s Working Groups on sustainable development.

By David Throsby | Wednesday February 20 2013

Fashion, architecture and computer games are all industries that depend on the arts economy.

In recent years there has been a growing policy interest in the economic potential of the arts. Economic policy in many countries in Europe, Asia, South America and elsewhere is paying increasing attention to the idea of the ‘creative economy’, the proposition that there exists in the economy a group of so-called ‘creative industries’ whose contribution to GDP, employment, exports etc. is growing more strongly that in traditional sectors such as manufacturing. Investment in these industries, so the argument runs, will pay handsome dividends in revitalising sluggish economic performance. This trend has had direct implications for the arts because the cultural industries, which include the arts, are a significant component of the creative economy.

Some people, including many artists, feel uncomfortable with a trend towards an emphasis on the economic role of the arts. The creative arts, they argue, are not an industry – artistic production has its own rationale that has nothing to do with economics. Artists are involved in pursuing whatever is their creative vision, and they resist the implication that their work can be treated simply as a commodity. So the question arises: How can we see the creative arts as contributors to the economy, but do so in a way that doesn’t constitute a sell-out to ‘economic rationalism’?

I suggest that it all depends on how you conceptualise the arts as a component of the cultural sector in the contemporary economy. We can interpret the contribution that the arts make to the economy as arising from the fact that they depend on creativity – the arts generate creative ideas and creative processes that feed other industries in the cultural sector like television, publishing, etc. and may flow on to other industries far removed from culture. The arts also train people in creative skills and develop creative talent that can be applied in many other industries.

So an appropriate way to interpret the arts in the economy is to put them at the very centre of a production system that derives benefit from the things the arts do. I have suggested a model of the cultural sector built along these lines. It sees the cultural industries as a series of concentric circles with the creative arts as the core, and with other industries producing output with cultural content represented as the various layers or circles around the core. The layers represent increasingly commercial industries as we move outward through the circles. The industries are classified into four groups ranging from industries with very high cultural content in the centre circle (music, theatre, visual art, etc.), to industries with a very small cultural content relative to commercial content in their output in the outermost circle (fashion, architecture, etc.).

The logic of this model is that ideas generated in the core diffuse outwards through the layers and beyond, stimulating creative output and innovation in other industries and sectors. Likewise creative talent and skills nurtured in the core find application in other industries through the movement of creative workers – artists, for example, may employ their creative skills in other industries in various ways such as visual artists designing websites, or actors involved in management training in big corporations, or craftspeople developing new materials and processes for use in industry.

So the message is this. Of course the arts are to be celebrated, encouraged and facilitated for fundamental artistic reasons, as well as for the wide range of cultural and social benefits that they bring. But we need to recognise that in addition they are a powerful economic sector, and the model of concentric circles helps us get this role into perspective. Not only do the creative arts deliver benefit to the economy through their contribution to GDP and job creation, but also they act as a source of creative ideas, skills and talents that have direct impacts on economic performance in the whole economy. This is as true in Australia as in any other country. The Discussion Paper for the National Cultural Policy that was released last year made much of these economic considerations in its discussion of government policy towards the arts. It seems likely that these ideas will help to shape the National Cultural Policy itself which we hope will be released some time soon.

David Throsby | [email protected]Professor David Throsby is Australia’s leading cultural economist. He is Professor of Economics at Macquarie University, has been a consultant to the World Bank, the OECD, FAO and UNESCO, and has chaired three Prime Minister’s Working Groups on sustainable development.